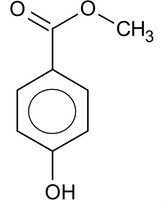

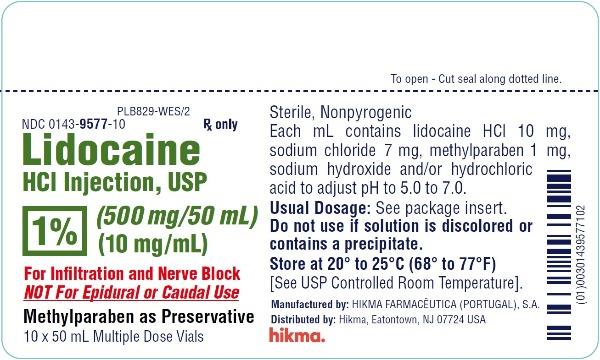

This is the third installment in the Dental Local Anesthetic Allergy series. Part I talked about reactions to certain older style dental anesthetics which are basically not used in dentistry any more. Part II addressed allergic and sensitivity reactions to preservatives and other components found in some local anesthetics.

This now leaves us with what we call true allergies. We use the term true to indicate it is a real allergic reaction to a dental local anesthetic – as opposed to a reaction to another component like sulfites – or other phenomenon.

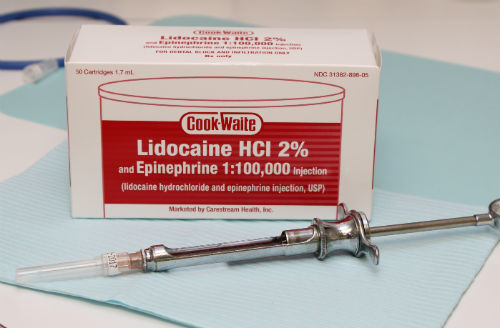

Lidocaine – A Modern Dental Local Anesthetic

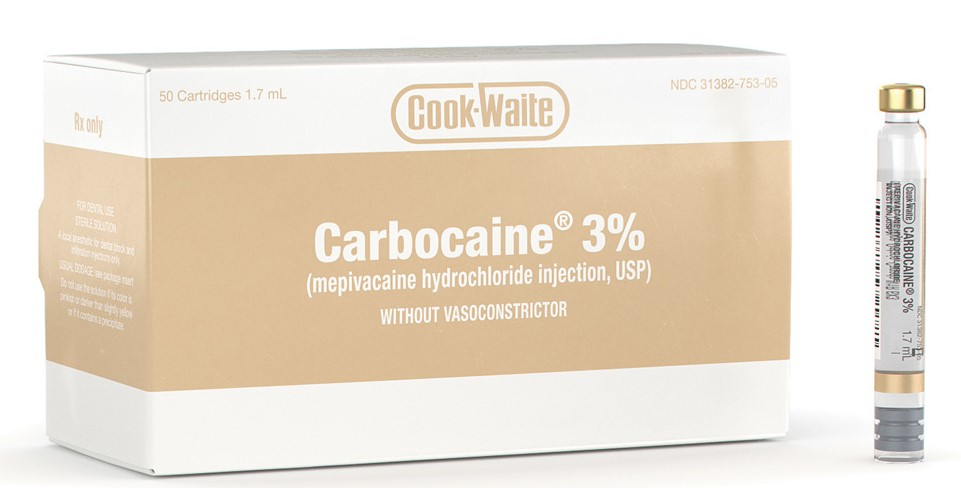

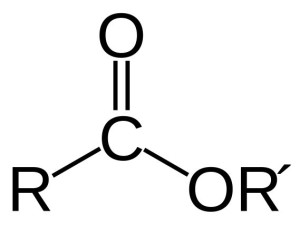

Lidocaine was first synthesized in 1943 and became widely available in the United States in 1948. Lidocaine was based on a new chemical structure of local anesthetics called amides. This class is chemically different than the previous “ester” ones such as novocaine and cocaine.

Lidodcaine with epineprhine is the most commonly used local anesthetic in the United States.

Immediately after its introduction, lidocaine took off in popularity for many reasons. One of the major reasons is because lidocaine did not cause allergic reactions with the frequency with which older anesthetics did. Because of this, the older class of anesthetics – novocaine included – were phased out – and by the 1980s basically no dentists in the United States were using novocaine anymore.

Allergies to Lidocaine and Other Amides

True allergies to lidocaine and other amide based anesthetics are rare. There is conflicting evidence on the prevalence of these reactions to lidocaine and other anesthetics.

- This 2013 paper documents a classic allergic reaction to lidocaine observed in a 12 year old child.

- This 2021 paper published in a prominent medical journal showed that of the patients referred to an allergy clinic for testing due to suspected allergies, only 3.5% were truly allergic.

- This 2012 paper published in a prominent British medical journal demonstrated that 1% of patients referred for testing showed a true allergy.

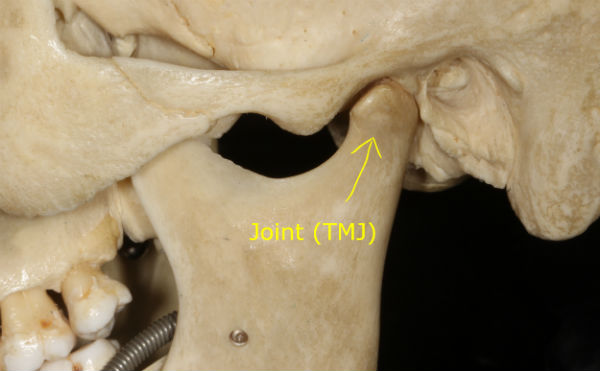

So, what might an allergy to the an injectable local anesthetic look like? Signs and symptoms could include:

- Pain and swelling at the injection site.

- Rapid heartbeat.

- Hives and/or itching (especially near the injection site).

- Cold/clammy skin.

- Nausea and possible vomiting.

- Wheezing and/or shortness of breath.

- A feeling of confusion and/or anxiety.

- And many other symptoms…

If/when this happens, it is best to get the opinion of the dentist/physician who administered the local anesthetic. He/she is the best equipped to identify a possible allergic reaction. From there, a referral for testing by an allergist may be recommended. If it turns out that you are allergic, there are options for how to receive dental care (read below).

Allergic vs. Adverse Drug Reactions

There mere sight of a needle can cause some people to pass out.

Other unpleasant reactions can occur after injections that are not allergic in origin. Generally speaking, those are called adverse drug reactions. These can include:

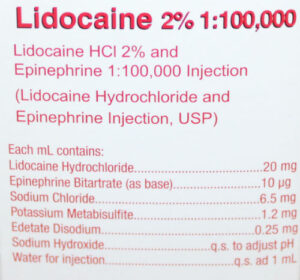

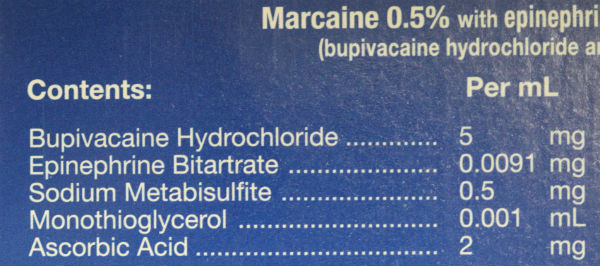

- A temporary rapid heartbeat and pounding in the chest. This can happen when epinephrine in the local anesthetic inadvertently leaves the injection site area and enters the bloodstream. It typically lasts a couple of minutes. If/when this occurs, you can ask your dentist in the future to use local that does not have epinephrine.

- Vasovagal syncope – a.k.a. – passing out. This can occur before, during, or after the injection. You typically feel weak, can gave blurred vision, feel very hot, and can momentarily lose consciousness.

- Hyper responder/Reaction of Unknown Origin – in these cases, generally speaking, you over-react to the effects of the local anesthetic. The findings can include: blurry or blacked out vision, rapid and strong heartbeat, acute hypertension, sweating, nausea, and other signs/symptoms.

Dental Treatment with a History of Allergy or Significant Reaction(s) to Local Anesthetics

We are one of the few offices in the entire United States that is able to treat patients who are unable to tolerate local anesthetics, we typically see patients coming to us in one of 3 categories:

- Those with a true allergy to one or more local anesthetic(s), confirmed by an allergist.

- Those who experienced a reaction and are too scared/tired to do testing by an allergist.

- Those who were tested by an allergist and experienced a severe but non-allergic reaction.

If you are one of these individuals, then you should not have local anesthetics administered to you. So what are your options:

- Get the dental treatment done without any local anesthetic. This can be quite uncomfortable though, as you can imagine.

- See a dentist who can provide dental treatment using Benadryl (diphenhydramine) as a local anesthetic with IV sedation. This is the technique we employ in our office and we have patients from all over the Northeast coming to see us. You can learn more here.

- As a last resort, the dental procedures can be done under general anesthesia. But there are many drawbacks to this approach.

Final Thoughts

So, over three separate posts, we’ve pretty much covered nearly everything there is to know about allergies to dental local anesthetics. As mentioned above, we offer treatment options that avoid the use of “-caine” local anesthetics. If you are interested, it is best to read about our approach here, or call us (203) 799 – 2929 or visit this page to request an appointment.